Chapter 13: Thermochemistry

Section 13-1: Enthalpy of Reaction, ΔH

Section 13-2: Estimating ΔH Using Bond Energies

Section 13-3: Calculating ΔH Using Hess's Law

Section 13-4: Calculating ΔH° Using Standard Enthalpies of Formation, ΔHf°

Section 13-5: Heat Transfer and the First Law of Thermodynamic

Section 13-6: Experiment - Determining the Specific Heat of a Metal Using Calorimetry

Section 13-8: ΔH for Changes of Physical State and Heating/Cooling Curves

Section 13-9: Experiment - Determining ΔHfusion of Ice

Chapter 13 Practice Exercises and Review Quizzes

Section 13-1: Enthalpy of Reaction, ΔH

Thermochemistry is

essentially the study of the heat released or absorbed by a reaction. A reaction that releases heat is said

to be exothermic, while a reaction

that absorbs heat is said to be endothermic. The heat released or absorbed by a

reaction under constant pressure conditions is known as the enthalpy of

reaction, ΔH. For an exothermic

reaction, ΔH will be negative, while ΔH will be positive for an endothermic

reaction. To express information

about the heat of a reaction, the value of ΔH is typically written after the

reaction in the unit kilojoules per mole as follows:

2 C2H6

(g) + 7 O2 (g) → 6 H2O(g) + 4 CO2 (g) ΔH = -3119 kJ/mol

Since ΔH is negative in this case,

we know that the reaction is exothermic and releases heat. We can use ΔH as a conversion factor in

the form

(where x

is the coefficient of the particular reactant or product being considered) to

convert between the actual amount reacted or produced and the actual amount of

heat released in a given reaction situation:

Sample Exercise 13A:

If 5.40 grams of ethane is burned

according to the combustion equation shown above, how much heat will be

released?

Solution:

Since we are considering the

reactant ethane, which has a coefficient of 2 in the equation above, x = 2 in

the conversion factor. We first

convert the grams of ethane to moles and then use the conversion factor to

convert to the amount of heat released:

If instead we know the actual

amount of heat in kJ involved in a given reaction situation and we wish to

convert to the amount reacted or produced, we first use the conversion factor

with kJ in the denominator and mol in the numerator, and then we can convert

moles to any desired unit:

Sample Exercise 13B:

The formation of gaseous phosphorus

trichloride is shown below:

P4

(g) + 6 Cl2 (g) → 4 PCl3

(g)

ΔH = -1207 kJ/mol

If 4.30 kJ of heat are released as

the formation reaction above proceeds, how many milliliters of gaseous

phosphorus trichloride, measured at 35°C and 712 torr, will be produced?

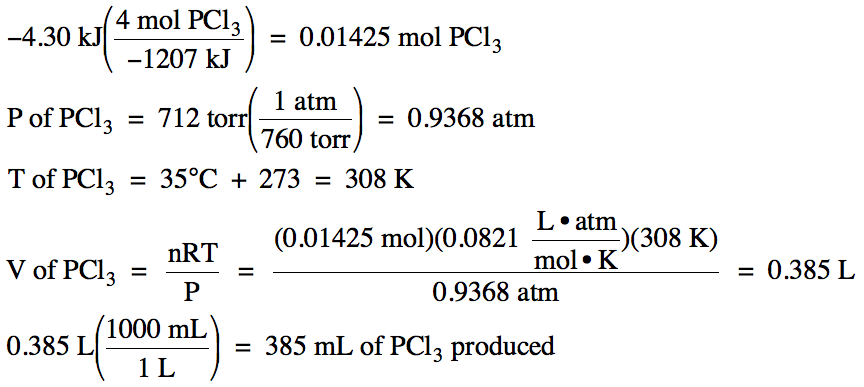

Solution:

The question specifies that heat is released, so we will need to make the given amount of

heat negative and begin the calculation with -4.30 kJ. Since we are considering the product

phosphorus trichloride, which has a coefficient of 4 in

the equation above, x = 4 in the conversion factor. We first use the conversion factor to convert to moles of

phosphorus trichloride, then

we use the Ideal Gas Law to find the volume of phosphorus trichloride

produced:

Section 13-2: Estimating ΔH Using Bond Energies

The following table shows a variety

of different average bond energies:

|

Bond |

Average Bond Energy (kJ/mol) |

|

C-C |

347 |

|

C=C |

614 |

|

C≡C |

839 |

|

C-H |

414 |

|

C-O |

360 |

|

C=O |

745 |

|

F-F |

157 |

|

F-N |

272 |

|

N-N |

163 |

|

N=N |

418 |

|

N≡N |

941 |

|

O-H |

464 |

|

O-O |

142 |

|

O=O |

498 |

Breaking covalent bonds requires

energy to be absorbed and is endothermic, whereas forming covalent bonds

releases energy and is exothermic.

For a chemical reaction in which all the reactants and products are gases,

we can estimate ΔH by adding the positive energies absorbed to break all bonds

in the reactant molecules to the negative energies released by the formation of

all bonds in the product molecules, as demonstrated in the following problem:

Sample Exercise 13C:

Use average bond energies to

estimate ΔH for the following reaction:

2 NF3

(g) → N2

(g) + 3 F2 (g)

Solution:

First, draw a Lewis structure for

each reactant and product molecule:

Then, being sure to take

coefficients into account, add the positive energies absorbed to break all

bonds in the reactant molecules to the negative energies released by the

formation of all bonds in the product molecules to find ΔH:

ΔH

(estimated) = (2x3)(N-F) – 1(N≡N) – 3(F-F)

= 6(272 kJ/mol) – 1(941 kJ/mol) – 3(157

kJ/mol) = 220 kJ/mol

Section 13-3: Calculating ΔH Using Hess's Law

When a reaction is reversed, the

sign of ΔH changes:

When all the

coefficients in a reaction are multiplied by the same number, ΔH is

multiplied by that same number as well:

Hess's Law essentially states that the unknown ΔH for a reaction

of interest can be determined by adding together the ΔH values from a series of

two or more other reactions if the other reactions add up algebraically to the

reaction of interest. For example,

if we wish to find ΔH for the reaction A → C, we can

add together the ΔH values from the following two reactions:

Reactions I and

II add up algebraically to reaction III because an equal amount of B

appears on both sides of the equation and, thus, can be canceled out.

In some cases, the given reactions

with known ΔH values may not add up to the reaction of interest with an unknown

ΔH. However, we may be able to

first reverse one or more of the given reactions (and, thus, switch the sign of

ΔH) and/or multiply all the coefficients of one or more of the given reactions

(and, thus, multiply ΔH by that same number) before adding the reactions to

find the unknown ΔH:

Sample Exercise 13D:

Calculate ΔH for the reaction C2H4

(g) + Cl2 (g) → C2H4Cl2

(l) using the following two reactions:

Solution:

Reactions I and

II do not add up algebraically to the reaction of interest. However, if we reverse Reaction I and

also multiply all the coefficients in Reaction I by ½ and then reverse

Reaction II, the new reactions will add up algebraically to the reaction of

interest because H2O (l), 2 HCl (g), and

½ O2 (g) will cancel out. Therefore, we can find the unknown ΔH by adding (-½ΔHI)

+ (-ΔHII):

Section 13-4: Calculating ΔH° Using Standard

Enthalpies of Formation, ΔHf°

The following table categorizes all

elements into their standard states at 1 atm and

25°C, which is essentially room temperature:

|

Gases |

Liquids |

Solids |

|

Cl2,

F2, H2, N2, O2 + noble gases |

Br2,

Hg |

I2 + all other elements |

C(graphite)

is considered the standard state of solid carbon because it is more stable than

the other allotrope, C(diamond).

When a formation reaction is

written, 1 mole of a given compound is produced on the right side and each

element present in the compound is shown separately in its standard state as a

reactant on the left side:

Formation

Reaction: standard state elements → 1 mol compound

To balance the equation while

keeping 1 mole of the compound on the right side, it may be necessary to use

fractions on the left side. For

example, the formation reaction for solid ammonium iodide would be:

Sample Exercise 13E:

Write the balanced formation

reaction, including physical states, for solid sucrose, C12H22O11.

Solution:

ΔH for a formation reaction is

known as the standard enthalpy of formation, ΔHf°,

and may be exothermic or endothermic.

However, ΔHf°

= 0 kJ/mol for all elements in their standard states.

ΔH for a reaction carried out at 1 atm is known as the standard enthalpy of reaction,

ΔH°. We can determine ΔH° for a

reaction using known ΔHf° values and

Hess's Law. For example, consider

the reaction aA + bB → cC + dD, where a and b are the

coefficients of the reactants A and B, and c and d are the coefficients of the

products C and D. Hess's Law

suggests that we can determine ΔH° for this reaction by adding the following

steps:

We can generalize this approach as

follows:

Sample Exercise 13F:

Calculate ΔH° for the reaction 2 H2S

(g) + 3 O2 (g) → 2 H2O

(l) + 2 SO2 (g) using the following information:

|

Compound |

ΔHf° (kJ/mol) |

|

H2S

(g) |

-20.6 |

|

H2O

(l) |

-285.8 |

|

SO2

(g) |

-296.8 |

Solution:

ΔHf° = 0 kJ/mol for the standard state element O2

(g), so ΔH° = [2(-285.8) + 2(-296.8) - 2(-20.6) - 3(0)] kJ/mol = -1124.0 kJ/mol

Section 13-5: Heat Transfer and the First Law of

Thermodynamics

Calorimetry is

essentially the measurement of heat in the laboratory. To calculate the quantity of heat (q)

in joules gained (positive value) when a substance increases in temperature or

lost (negative value) when a substance decreases in temperature, without a

change in physical state, we multiply the mass (m) of the substance in grams by

the specific heat (s) of the substance in J/g•°C and

also by the temperature change of the substance (tfinal

– t initial) in °C:

q = msΔt = ms(tf – ti)

Sample Exercise 13G:

The specific heat of copper metal

is 0.385 J/g•°C. How much heat in joules and in kilojoules is lost when a 165

gram sample of copper metal is cooled from 98°C to 26°C?

Solution:

The First Law of Thermodynamics has been referred to as the Law of

Conservation of Energy and essentially states that energy can neither be

created nor destroyed. In calorimetry experiments, if one substance at a higher

temperature is placed together with a second substance at a lower temperature

in an insulated container that does not allow heat entry or exit, both

substances will eventually reach the same final temperature. Furthermore, the First Law of

Thermodynamics suggests that the amount of heat lost by the higher temperature

substance will be exactly equal to the amount of heat gained by the lower

temperature substance:

qlost = -qgained

Note that, although the magnitude of

heat will be equal, qlost is

exothermic and will have a negative sign, whereas qgained

is endothermic and will have a positive sign.

Section 13-6: Experiment - Determining the Specific

Heat of a Metal Using Calorimetry

The specific heat of water is known

to be 4.18 J/g•°C. If a metal with unknown specific heat but known mass and

initial temperature is mixed in an insulated calorimeter, such as a securely-covered Styrofoam coffee cup, with a known mass of

water that also has a known initial temperature, the specific heat of the metal

can be determined as follows:

Sample Exercise 13H:

In an insulated calorimeter, a 175

gram piece of aluminum metal originally at 304°C was added to 925 grams of

water originally at 22°C. The

final temperature of the aluminum-water mixture was 33°C. Determine the specific heat of

aluminum.

Solution:

According to the First Law of

Thermodynamics, the amount heat lost by the aluminum metal will be exactly

equal to the amount of heat gained by the water (but opposite in sign):

qAl lost = -qwater gained

We first calculate the amount of

heat the water gained and then switch the sign to find the amount of heat the

aluminum lost, after which we can calculate the specific heat of aluminum:

If we know the masses, specific heats, and initial temperatures of both the metal and the water, we can calculate the final temperature in the calorimeter after mixing, as demonstrated below in Practice Exercise 13-9.

Section 13-7: Experiment – Determining ΔH Using

Calorimetry

When a solid ionic compound (salt)

is dissolved in water, the cations and anions become

separated from each other and are hydrated as water molecules surround the ions

to create ion-dipole interactions. If this process is exothermic, the reaction

particles will release heat into the surrounding mixed solution and increase

the temperature of the solution.

If this process is endothermic, the reaction particles will absorb heat

from the surrounding mixed solution and decrease the temperature of the

solution. We can determine the

heat lost or gained by the reaction, qrxn,

by first calculating the heat lost or gained by the surrounding solution, qsoln, and then switching the sign:

qrxn = -qsoln

After finding qrxn

and converting to kilojoules, we can divide by the moles of salt dissolved to

find ΔH for the process in kJ/mol of salt dissolved:

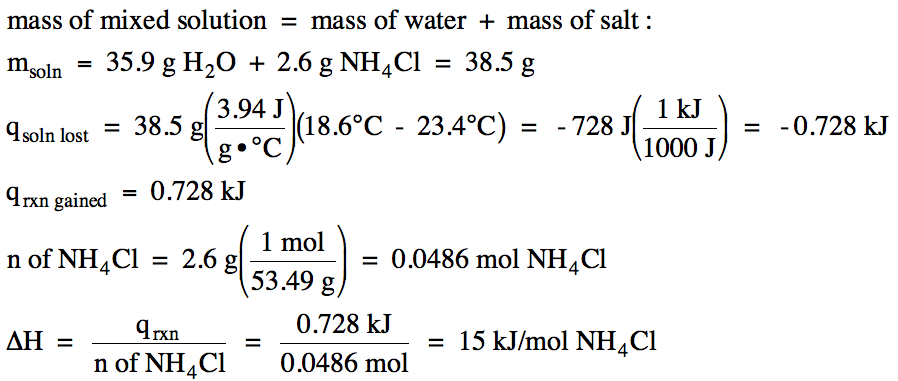

Sample Exercise 13I:

In an insulated calorimeter, 2.6 grams of solid ammonium chloride at 23.4°C was dissolved in 35.9 grams of water also at 23.4°C, after which the final temperature of the mixed solution was 18.6°C. If the specific heat of the mixed solution was 3.94 J/g•°C, determine ΔH for the dissolving process NH4Cl (s) → NH4Cl (aq) in kJ/mol NH4Cl.

Solution:

Since the temperature of the mixed

solution decreased, the mixed solution lost heat and the reaction particles

gained heat in an endothermic reaction with ΔH > 0:

qrxn gained = -qsoln lost

We first calculate the amount of

heat the mixed solution lost and then switch the sign to find the amount of

heat the reaction particles gained, after which we can convert to kilojoules

and divide by the moles of ammonium chloride to find ΔH for the dissolving

process NH4Cl (s) → NH4Cl

(aq):

For neutralization reactions

between an aqueous acid and an aqueous metal hydroxide, the process of

determining ΔH by calorimetry is similar to that used

for the dissolving of ionic salts, but the calculation typically differs in the

following two ways:

1. Instead of masses being given,

we may be given the volume of each solution being mixed, which we then can add

to obtain the total volume of the mixed solution that absorbs heat from or

releases heat into the reaction particles. If we are given the density of the mixed solutions, we can

multiply by the volume of the mixed solutions to obtain the mass of the mixed

solutions that is necessary in the calculation of qsoln.

2. In the final step, we divide qrxn by the moles of a specified product formed in

the reaction from the limiting reagent to obtain ΔH for the reaction.

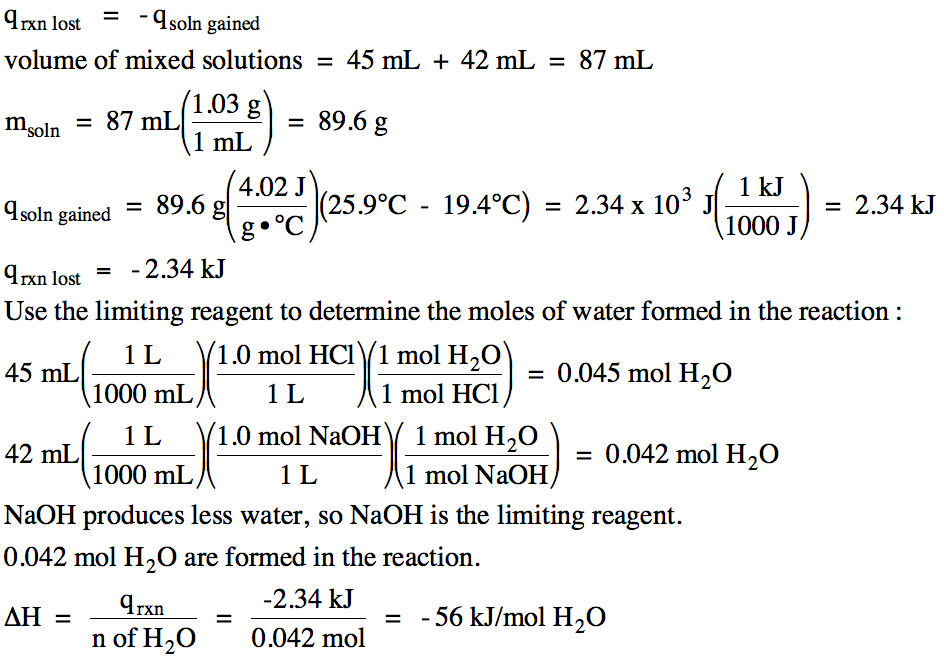

Sample Exercise 13J:

In an insulated calorimeter, 45 mL of 1.0 M hydrochloric acid was mixed with 42 mL of 1.0 M sodium hydroxide, with both solutions

originally at 19.4°C. The final

temperature of the mixed solutions was 25.9°C. The density of the mixed solutions was 1.03 g/mL and the specific heat of the mixed solutions was 4.02 J/g•°C. Write a

balanced molecular equation, including physical states, and determine ΔH for

the neutralization reaction in kJ/mol of water formed.

Solution:

HCl (aq) + NaOH

(aq) → H2O

(l) + NaCl (aq)

Since the temperature of the mixed

solutions increased, the mixed solutions gained heat and the reaction particles

lost heat in an exothermic reaction with ΔH < 0:

Section 13-8: ΔH for Changes of Physical State and

Heating/Cooling Curves

Changes of physical state occur at

a constant temperature. The

endothermic change from solid to liquid is known as fusion and occurs at the

melting point of the substance. To

calculate the amount of heat absorbed when a given amount of a substance is

melted, we multiply the moles melted by ΔH for the fusion process:

q = (nmelted)(ΔHfusion)

If the same amount of the substance

was frozen from a liquid to a solid rather than melted, the magnitude of heat

involved would be exactly the same, but heat would be released in the

exothermic process and q would be negative:

q = (nfrozen)(-ΔHfusion)

The endothermic change from liquid

to gas is known as vaporization and occurs at the boiling point of the

substance. To calculate the amount

of heat absorbed when a given amount of a substance is vaporized, we multiply

the moles vaporized by ΔH for the vaporization process:

q = (nvaporized)(ΔHvaporization)

If the same amount of the substance

was condensed from a gas to a liquid rather than vaporized, the magnitude of

heat involved would be exactly the same, but heat would be released in the

exothermic process and q would be negative:

q = (ncondensed)(-ΔHvaporization)

A heating curve is a graph that

depicts the changes in temperature and physical state that occur over time as

heat is absorbed by a substance.

The following sketch represents the general format of a heating curve

for a substance originally below the melting point in the solid state being

heated until it is a gas above the boiling point:

A cooling curve is a graph that

depicts the changes in temperature and physical state that occur over time as

heat is released by a substance.

The following sketch represents the general format of a cooling curve

for a substance originally above the boiling point in the gas state being

cooled until it is a solid below the melting point (same temperature as

freezing point):

Note that heating and cooling

curves may encompass a less narrow temperature range and, therefore, may not

include all five of the distinct segments shown in the two sketches above.

Sample Exercise 13K:

Consider the following data for H2O:

Melting

Point = 0.0°C

Boiling

Point = 100.0°C

ΔHfusion = 6.01 kJ/mol

ΔHvaporization = 40.8 kJ/mol

Specific

Heat of Ice = 2.03 J/g•°C

Specific

Heat of Water = 4.18 J/g•°C

Specific

Heat of Water Vapor = 1.99 J/g•°C

Sketch a heating curve that depicts

ice at -25.0°C being heated until the temperature reaches 125.0°C and then

calculate the total amount of heat in kilojoules absorbed when 175 grams of H2O

undergoes this process.

Solution:

We first calculate the amount of

heat absorbed along each of the five distinct segments of the heating curve and

then add the five heat values together to find the total heat absorbed:

qtotal = 8.881 kJ

+ 58.37 kJ + 73.15 kJ + 396.2 kJ + 8.706 kJ = 545 kJ

Section 13-9: Experiment – Determining ΔHfusion of Ice

Given the specific heats of ice and

water in the previous problem, we can determine ΔHfusion

of ice in the laboratory by mixing in an insulated calorimeter a known mass of

ice at a known original temperature below 0°C with a known mass of water at a

known original temperature above 0°C.

If we use enough water and/or a high enough original water temperature,

all the ice will melt and the final temperature in the calorimeter will be

above 0°C. The sketch below

depicts the heating curve for the ice as its temperature rises to its melting

point, the ice melts, and then the temperature of the melted ice rises to the

final temperature. On the same

sketch, the cooling curve for the water as it cools from its original

temperature to the final temperature is also included:

The heat lost by the water as it

cools to the final temperature will be equal in magnitude but opposite in sign

to the total heat gained by the ice in the three segments of the heating curve

above, which will allow us to determine ΔHfusion

of ice:

Sample Exercise 13L:

In an experiment to determine ΔHfusion of ice, a student added 29.04 grams of

ice originally at -15.1°C to 97.91 grams of water originally at 41.9°C in an

insulated calorimeter. If the

final temperature in the calorimeter was 13.2°C, calculate the experimentally

determined ΔHfusion of ice.

Solution:

The heating curve for the ice +

cooling curve for the water is:

Chapter 13 Practice Exercises and Review Quizzes:

13-1) The

decomposition of ammonia gas into nitrogen gas and hydrogen gas is endothermic:

2 NH3

(g) → N2

(g) + 3 H2 (g) ΔH = 92 kJ/mol

If 762 mL

of hydrogen gas, measured at 325°C and 792 mmHg, is formed in the reaction

above, how much heat will be absorbed?

Click for Solution

13-1)

13-2) Consider

the following reaction:

2 ZnS (s) + 3 O2 (g) → 2 ZnO

(s) + 2 SO2 (g) ΔH = -878 kJ/mol

What mass of solid ZnS, in kilograms, must react according to the equation

above in order for 5.41 x 103 kJ of heat to be released?

Click for Solution

13-2) Heat is released = must start

with -5.41 x 103 kJ:

13-3) For the reaction 2 CH3OH (g) + 3 O2 (g) → 2 CO2 (g) + 4 H2O (g), estimate ΔH using average bond energies.

Click for Solution

13-3)

Lewis

structures:

ΔH

(estimated) = (2x3)(C-H) + (2x1)(C-O) + (2x1)(O-H) + (3x1)(O=O)

-

(2x2)(C=O) - (4x2)(O-H)

= 6(414

kJ/mol) + 2(360 kJ/mol) + 2(464 kJ/mol) + 3(498 kJ/mol)

- 4(745

kJ/mol) – 8(464 kJ/mol) = -1066 kJ/mol

13-4) Calculate ΔH for the reaction

4 NH3 (g) + 5 O2 (g) → 4 NO (g) +

6 H2O (l) using the following three reactions:

Click for Solution

13-4) Reactions I + II + III do not

add up algebraically to the reaction of interest. However, if we multiply all the coefficients in Reaction I

by 3, if we reverse Reaction II and multiply all coefficients in Reaction II by

2, and if we multiply all the coefficients in Reaction III by 2, the new

reactions will add up algebraically to the reaction of interest because 2 N2

(g) and 6 H2 (g) will cancel out. Therefore, we can find the unknown ΔH by adding (3ΔHI)

+ (-2ΔHII) + (2ΔHIII):

13-5) Write

the balanced formation reaction, including physical states, for liquid tribromomethane, CHBr3.

Click for Solution

13-5)

13-6) Calculate ΔH° for the

reaction 2 C4H10 (g) + 13 O2 (g) → 10 H2O(g)

+ 8 CO2 (g) using the following information:

|

Compound |

ΔHf° (kJ/mol) |

|

C4H10

(g) |

-126.5 |

|

H2O

(g) |

-241.8 |

|

CO2

(g) |

-393.5 |

Click for Solution

13-6) ΔH° = [10(-241.8) + 8(-393.5)

- 2(-126.5) - 13(0)] kJ/mol

13-7) The

specific heat of lead metal is 0.130 J/g•°C. How much heat in joules and in

kilojoules is gained when a 225 gram sample of lead metal is heated from 125°C

to 241°C?

Click for Solution

13-7)

13-8) In

an insulated calorimeter, a 225 gram piece of iron metal originally at 463°C

was added to 845 grams of water originally at 27°C. The final temperature of the iron-water mixture was 39°C. Determine the specific heat of iron.

Click for Solution

13-8)

13-9) The specific heat of titanium metal is 0.54 J/g•°C. In an insulated calorimeter, a 265 gram piece of titanium metal originally at 285°C was added to 645 grams of water originally at 26°C. Determine the final temperature of the titanium-water mixture.

Click for Solution

13-10) In

an insulated calorimeter, 12.7 grams of solid calcium chloride at 21.4°C was

dissolved in 129.1 grams of water also at 21.4°C, after which the final

temperature of the mixed solution was 38.3°C. If the specific heat of the mixed solution was 3.89 J/g•°C, determine ΔH for the dissolving process CaCl2

(s) → CaCl2

(aq) in kJ/mol CaCl2.

Click for Solution

13-11) In an insulated calorimeter,

85.6 mL of 2.55 M nitric acid was mixed with 94.3 mL of 2.51 M potassium hydroxide, with both solutions

originally at 22.6°C. The final

temperature of the mixed solutions was 39.1°C. The density of the mixed solutions was 1.04 g/mL and the specific heat of the mixed solutions was 3.98 J/g•°C. Write a

balanced molecular equation, including physical states, and determine ΔH for

the neutralization reaction in kJ/mol of water formed.

Click for Solution

13-11) HNO3 (aq) + KOH (aq) → H2O (l) + KNO3

(aq)

Since the temperature of the mixed

solutions increased, the mixed solutions gained heat and the reaction particles

lost heat in an exothermic reaction with ΔH < 0:

13-12) Consider

the following data for ethanol, C2H5OH:

Melting

Point = -114°C

Boiling

Point = 78°C

ΔHfusion = 5.0 kJ/mol

ΔHvaporization = 42.6 kJ/mol

Specific

Heat of Liquid Ethanol = 2.5 J/g•°C

Sketch a cooling curve that depicts

ethanol vapor at 78°C being cooled until solid ethanol is formed at -114°C and

then calculate the total amount of heat in kilojoules released when 55 grams of

ethanol undergoes this process.

Click for Solution

13-12) In this case, there are only

three distinct segments on the cooling curve because the ethanol vapor is

already at the boiling point to start and the solid ethanol formed does not

cool below the melting/freezing point:

We first calculate the amount of

heat released along each of the three distinct segments of the cooling curve

and then add the three heat values together to find the total heat released:

Click for Review Quiz 1 Answers